|

Imagine going into war abroad coming under a hail of enemy fire to fight

against fascism in Europe and returning home to battle for your own democratic

freedoms. This was the reality for Col. Charles McGee and other minorities

during World War II. In 1942 McGee joined the Army and signed up for a pilot

slot in an experimental program located at Tuskegee Army Airfield, which allowed

African-Americans to train to become airmen for the first time in U.S. history.

|

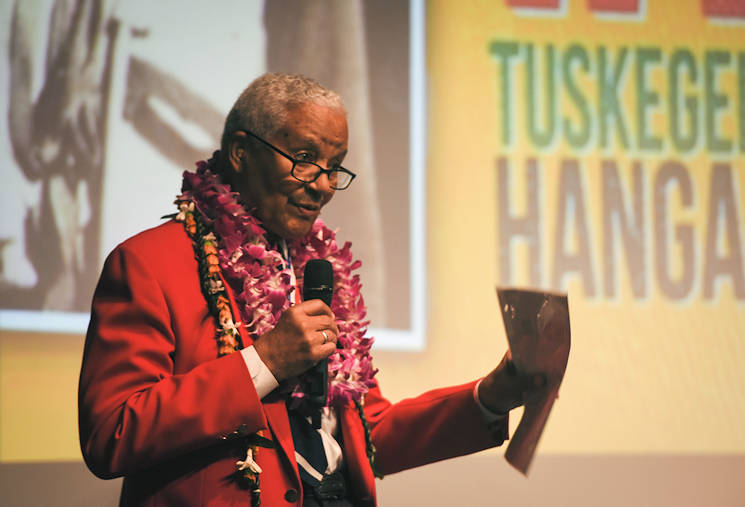

February 3, 2017 - Retired U.S. Air Force Col. Charles McGee stands

in the Pacific Aviation Museum, Ford Island, Hawaii. McGee, a

Tuskegee Airman, who served as a pilot during World War II, the

Korean War and Vietnam War, gave a presentation at the Pacific

Aviation Museum geared towards youth entitled, “In His Own Words.”

(Department of Defense photo by U.S. Navy Petty Officer 2nd Class

Aiyana S. Paschal)

|

“Well, at the time I hadn’t thought about it like oh we’ll go down Tuskegee

and set the world on fire. It was just a matter of being able to participate and

certainly, for me, it was a joy to be on the flying side of things,” said McGee.

I enjoyed doing that and that’s what I’d like to pass on. I think it’s every

citizen’s right and certainly a responsibility to serve the country in one way

or another, and I think going forward that helps preserve the freedoms we so

much enjoy.” Prior to World War II minorities were only allowed to perform

service type jobs. McGee recalls a 1925 Army War College Report titled “The Use

of Negro Manpower in War”, which made assumptions about African Americans

capacity to serve in the military. ‘The Negro is by nature subservient and

believes himself to be inferior to the white man. He is most susceptible to the

influence of crowd psychology,” said McGee. ‘He cannot control himself in the

face of danger to the extent the white man can. He has not the initiative and

resourcefulness of the white man. He is mentally inferior to the white man’,

McGee said. “This report said because of physical qualification and of course

that meant service you know dig ditches, cook food, drive trucks, but doing

anything technical impossible.” McGee Graduated flight school on June 30,

1943, and was assigned to an all-black squadron called 332nd Fighter Group in

Naples, Italy. Although the men and women of the squadron landed their shot at

serving as airmen, they were still segregated from their white counterparts and

as McGee described “treated like second-class citizens”. “Well, the challenge

pretty much at the time was being accepted based on our ability and so on rather

than the fact that there were those who felt we didn’t have the brain power or

the fortitude to participate in a successful way,” said McGee However, McGee

and his unit quickly gained notoriety through their successful long-range bomber

escort missions. Their flawless execution of their mission earned them the

respect from the white bomber crews and made them a formidable adversary to the

German Luftwaffe pilots. By the end of 1944, McGee had 137 combat missions under

his belt. “Fortunately once given the opportunity we were able to disprove

that because it’s all about first, having an education and developing a talent

and found out we could perform successfully,” said McGee. Charles McGee and

the 332nd’s commitment to service did not go unnoticed by the nation. In 1947

the Army Air Corps started abandoning its policies that promoted segregation.

One year later President Harry Truman signed an executive order to abolish

racial discrimination in the United States Armed Forces. “Well, I didn’t

realize that was happening when I got the opportunity to serve but realized what

it meant because the experience gave the air force the background to make a

decision that affected all of our services and affected the country,” said

McGee. I was just glad to serve and doubly glad that it turned out to be that

important even though that wasn’t a goal for my reason of serving at the time.”

McGee is committed to passing down the first-hand experience of history to

future generations so that they may never forget the lessons learned. “I

enjoy talking to students and enjoy getting their questions and answers because

I realize the value of the lessons that sustained us if you will through those

periods that we don’t want to be repeated in many ways are still important for

their growing up and taking part in the future of our country,” said McGee. So

it’s always a pleasure to talk to students and hopefully get them to realize

that they are the future of their country and so their attitudes are all very

important.” As a result of Charles McGee and other trailblazers like him,

more than one million African-Americans served in World War II. He has a total

of 409 aerial combat missions flown, which is the highest Air Force record.

Today, the United States Armed Forces continues to strive for diversity by

opening opportunities for more citizens to serve.

By U.S. Navy Petty Officer 2nd Class Jerome Johnson

Defense Media Activity

Provided

through DVIDS

Copyright 2017

Comment on this article |