|

In the late 1790s, the United States and Revolutionary France

began fighting an undeclared naval war known as the “Quasi War.”

With only a small naval force available at the time, U.S.

authorities called on the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service to protect

American merchantmen and defend them against French privateers.

In the early 1790s, the nation's revenue cutters were small

lightly armed vessels, cruising for only days at a time out of their

homeports. The service quickly built a class of small warships, or

super-cutters, which matched or exceeded the speed and armament of

enemy privateers. This new class of cutters included Eagle,

Pickering, and Scammel, which all participated in combat operations

during the Quasi War. Pickering was one of the standouts of this

class, capturing nearly 20 prizes and privateers, including l'Egypte

Conquise. The French privateer carried almost double Pickering's

weapons and crew, and surrendered only after a brutal 9-hour gun

battle. However, sailing under Master Hugh George Campbell, Eagle

commanded the best wartime record of captures for any U.S. vessel.

In August 1798, Campbell arrived in Philadelphia to take

possession of Eagle for the Revenue Cutter Service and prepare her

for sea. The 187-ton vessel measured 58 feet on the keel, with a

20-foot beam and 9-foot hold. Eagle carried 14 6-pound carriage guns

on her main deck. At about 6 feet in length and weighing around 700

pounds apiece, these 6-pounders required a high degree of skill,

training and physical strength to maintain and operate. The cutter

was likely pierced with 16 gun ports, two extra for ranging cannon

forward and handling anchor lines through the bow.

|

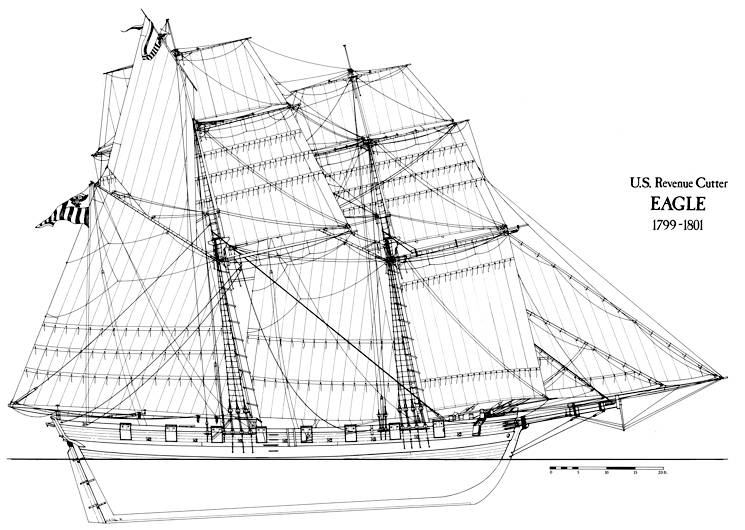

Based on records and documents, this modern profile view shows the

US Revenue Cutter (USRC) Eagle, which fought in the Quasi-War with France.

(Coast Guard Collection 1799)

|

Problems had emerged before Campbell arrived in

Philadelphia adding weeks to Eagle's departure on her first war

cruise. The large cutter required a complement of no less than 70

men to sail her, man her guns, board enemy ships and supply prize

crews for captured vessels. A yellow fever epidemic had struck the

city and regulations forbidding enlistment of black seamen both

delayed recruiting. Under orders from Navy Secretary Benjamin

Stoddert, Campbell did his best to “Enlist none but healthy white

men, and give preference to Natives if they are to be had.” The

cutter's crew ultimately included Campbell, mates (first, second and

third), boatswain, carpenter, gunner, able seamen, ordinary seamen,

cook, steward, boys and a contingent of 14 marines.

Local

shortages of war material also delayed Eagle's deployment. Before

sailing for the theater of operations, Eagle required four months'

worth of provisions and two months' supply of water. Philadelphia's

naval suppliers had to provide military stores, such as powder,

flints, cutlasses, pistols, blunderbusses and gun carriages. Eagle

required 40 cannon balls per 6-pound gun, or 560 cannon shot, which

required additional time to acquire. By late November, Campbell was

fully provisioned and ready to go in harm's way with the swiftest

vessel in the American fleet.

Eagle's deployment came none

too soon as rumors spread that French privateers were cruising in

southern waters, causing concern among American merchants and

shippers. Campbell received orders to patrol off South Carolina and

Georgia coasts, so he raised anchor and set a course down the

Delaware River. Campbell's mission showed the U.S. flag along the

coast and proved a success in the eyes of nervous merchants, but

Eagle encountered no enemy cruisers during her deployment. In

January 1799, Campbell received new orders to rendezvous with the

American naval squadron based at Prince Rupert's Bay, Dominica.

Campbell set sail for the rendezvous, initiating a 2-year

rampage against enemy shipping and privateers. On March 2,

before falling in with the American squadron, Eagle re-took

from a French prize crew the captured American sloop Lark.

As was the custom at the time, cutters and Navy ships

received prize money for capturing enemy vessels, or a

smaller amount of salvage money for re-capturing prize

vessels. Lark proved the first of many re-taken vessels to

line the pockets of Campbell and his men with salvage money.

Also in March, Congress enacted legislation that brought the

Revenue Cutter Service under the control of the U.S. Navy.

After this legislation became law, revenue cutters would

forever serve as part of the Navy during armed conflicts, as

modern Coast Guard cutters do today.

In mid-March

1799, Campbell reported for duty to squadron commander John

Barry, captain of the 44-gun frigate USS United States.

Eagle fell in with the rest of the squadron, including her

sister ship Pickering, en route to Prince Rupert's Bay. By

this time, Caribbean waters had become a lawless place of

privateers and their prey; and, within weeks of the

rendezvous, Campbell had re-captured a second prize ship and

run ashore a French privateer at Barbuda.

|

This painting of the US Revenue Cutter Eagle capturing privateer Le Bon Pierre

in 1799 illustrates the activities carried out by revenue cutters during the Quasi-War.

(Coast Guard Collection)

|

At the time of Eagle's entry into the war, enemy privateers

operated out of French possessions, such as Guadeloupe and St.

Martin. On Friday, April 5, Eagle gave chase to the Guadeloupe-based

privateer Le Bon Pierre, pierced for 10 cannon, but mounting only

four with a 55 man crew. The sloop fled and dumped two guns

overboard to speed her escape. However, after a five hour chase,

Eagle overhauled the privateer, whose crew offered no resistance.

Campbell placed aboard the privateer a prize master and prize crew

who sailed Le Bon Pierre to Savannah for adjudication. The Revenue

Cutter Service purchased the sloop and converted her into the cutter

Bee to serve the Savannah station, giving Campbell and his men

shares of the privateer's handsome $2,000 adjudication value.

In mid-April, Eagle joined the 44-gun frigate USS Constitution

(a warship Campbell would one day command) to escort 33 British and

American merchantmen out of the Caribbean. During such convoy

operations, it was Eagle's duty to fend off privateers and cruisers

attempting to “cut out” merchantmen from the convoy. Eagle

encountered at least one “strange sail” during the mission, but no

merchantmen were lost. At the end of April, Eagle patrolled with

revenue cutter Virginia and the 18-gun brig USS Richmond. Together,

they captured the French schooner Louis before Eagle returned to

base at Prince Rupert's Bay.

|

Image of marine artist Peter Rindlisbacher's painting of the

USRC Eagle and USS Constitution escorting a convoy out of the Caribbean

during the Qqasi War with France in the 1799. (Image provided by U.S. Coast Guard Academy Library)

|

Early in May, Eagle arrived at the squadron's new base at

Basseterre, St. Kitts, located north of Guadeloupe. From there, she

re-joined USS Richmond and patrolled windward of Barbuda and

Antigua. On May 15, the two brigs encountered the French privateer

Reliance of 14 guns and 75 men in consort with two prize ships.

These prize ships were the Massachusetts brig Mehitable, sailing

home to Newburyport from Suriname; and the New Bedford whaler Nancy

returning home from a one year voyage to the South Pacific.

Outnumbered and outgunned, Reliance fled, leading the Richmond on a

14-hour chase, after which the privateer escaped under cover of

darkness. Meanwhile, Eagle re-captured both Mehitable and Nancy,

taking prisoner their French prize crews. Nancy alone carried tons

of spermaceti oil valued at $50,000, a large fortune whose salvage

value was shared out to her captors.

|

This painting held by the U.S. Coast Guard Academy shows the

USRC Eagle

re-capturing prize ships Nancy and Mehitable in May 1799. (Image

provided by U.S. Coast Guard Academy Library)

|

May 1799 proved lucrative for Campbell, including the final days

of the month. On Wednesday, May 29, Eagle partnered with the 20-gun

ship USS Baltimore to capture the privateer schooner Syren of four

guns and 36 men. Later that day, Eagle and frigate USS United States

re-captured the American sloop Hudson. These captures added to

Campbell's reputation as a combat commander and his net worth,

greatly padding the wealth he would amass over the course of the

war.

Spring 1799 had been a successful season for Campbell, but summer

brought new missions. On June 13, Eagle and Richmond served as

escorts for a convoy sailing from St. Kitts north toward Bermuda.

The two warships left the convoy near the Virginia coast and July

saw Eagle laid up in Norfolk, undergoing repairs and replacing

personnel. Meanwhile, American squadron commodore Thomas Tingey

wrote dispatches from St. Kitts to the Secretary of the Navy begging

for the speedy return of his top combat commanders, including

Campbell. On July 27, Campbell received a U.S. Navy commission as

master and commandant. On August 2, the Treasury Department

transferred official control of the cutter and its crew to the Navy.

In early August, Campbell received orders to sail south from

Norfolk and rejoin the American squadron. By early September, Eagle

had returned to St. Kitts and set sail with the 20-gun ship USS

Delaware, capturing the French merchant sloop Reynold, laden with

sugar and molasses. On September 19, Eagle encountered a French

privateer towing the American brig North Carolina. Eagle drove off

the privateer and retook the brig. On October 2, in company with

Commodore Tingey's 24-gun sloop USS Ganges, Eagle captured the

French merchant schooner Esperance, carrying sugar and coffee.

Two days after capturing Esperance, while anchored at St.

Bartholomew's, Campbell became party to one of the most notorious

mutinies of the day. Two weeks into a voyage to St. Thomas, three

seamen took control of the schooner Eliza of Philadelphia. The

mutineers murdered the mate, a seaman and the supercargo; however,

they failed to kill the captain, who kept the ship's only firearms

locked in his cabin. Armed with his pistols, the captain managed to

entrap the three men below decks, retake the ship and sail

single-handed for 13 days before encountering the Eagle. Campbell

assisted the merchant captain and put the three mutineers in irons.

He later transferred the men to the USS Ganges bound north for

Philadelphia. Upon the American warship's arrival, local authorities

tried and convicted the men on charges of murder and piracy, and

hanged them on Wind Mill Island across the Delaware River from the

city.

Over the next six months, Campbell enjoyed a string of

successes: December 5, the Eagle crew retook the brig George;

January 2, they recaptured the brig Polly; the 10th, Eagle together

with the 28-gun frigate USS Adams, captured the French privateer

Fougueuse, of two guns and 50 men, and recaptured the American prize

ship Aphia; February 1, Eagle captured the French schooner

Benevolence; on March 1, it recaptured the American schooner Three

Friends; on April 1, it captured the French privateer Favorite; on

May 7, Eagle retook the American sloop Ann; and, three days later,

she recaptured the American schooner Hope.

Campbell's combat

record rested on his sound leadership, the proper maintenance of his

ship, and care of his crew. But combat also required good judgment.

Campbell had to take risks and know when to press an attack and when

not to. In early February 1800, he spotted two strange vessels,

pursued them, and found the ships to be French privateers with a

fighting strength twice his own. He outsailed the privateers, but

suffered numerous hits from their guns while making good his escape.

In June, Eagle encountered an enemy privateer with three prize ships

off St. Bartholomew's. Campbell attacked and Eagle received severe

damage to its sails and rigging before the privateer fled.

Meanwhile, the three prize ships ran ashore, robbing Campbell of

their salvage value.

|

Campbell's faded headstone at the Congressional Cemetery, near the Washington Navy Yard, is the only memorial to his heroic exploits and service to his country.

(Image courtesy of Historic Congressional Cemetery, Washington, D.C.)

|

|

In June 1800, Eagle captured two French ships and a third in

August. These vessels would be the last captures of Campbell's

two-year campaign in the Caribbean. Despite spending considerable

time escorting convoys and refitting at home, Campbell's Eagle had

captured, or assisted in the capture, of 22 privateers, prize ships

and enemy merchantmen.

Campbell not only had command presence and seafaring ability, he

was lucky. By September 1800, Eagle was in bad shape with half her

copper sheathing gone and much of her wood planking infested with

shipworms. Campbell received orders to escort a convoy north,

together with the 26-gun sloop USS Maryland, and then sail home for

refitting and hull maintenance. While Eagle rode at anchor awaiting

her convoy's 50 merchantmen to assemble at St. Thomas, a major

hurricane swirled to the north, forcing a number of American

warships to fight for their survival. Top heavy with thick masts and

spars, and dozens of large cannon, the frigate USS Insurgent was

probably the storm's first victim. She vanished from the sea's

surface with her entire crew of 340 men. The next victim must have

been Eagle's sistership Pickering, which had recently triumphed over

the privateer l'Egypte Conquise.

But the victor became the vanquished as the heroic cutter lost

her battle with Mother Nature. A day later all that remained of

Pickering was an overturned hull afloat in the calm seas. Another of

Eagle's sisterships, Scammel, survived the storm only by dumping her

cannon and excess gear. What the enemy had failed to do against the

American squadron in months of naval warfare, the violent storm

executed in just hours. After the hurricane passed, Campbell and his

crew raised anchor and sailed north with the convoy not knowing

their course took them over the watery graves of 400 American souls

lost with the Pickering and Insurgent.

After Campbell completed this final escort mission, he set a

course for Delaware Bay. On Sunday, September 28, Eagle dropped

anchor at Newcastle, Delaware, and Campbell's command of the cutter

came to an end. After refitting in Philadelphia, Eagle served a

final tour in the Caribbean under another captain.

But, with the conflict nearing an end, the brig saw little

action. After the war ended, the Navy scaled back the fleet to its

larger warships in the interests of economy. Eagle sailed for

Baltimore to be decommissioned and on Wednesday, June 17, the Navy

sold her for the sum of $10,585.73. Five more cutters named “Eagle”

would serve in the Revenue Cutter Service and modern Coast Guard,

including the Barque Eagle, the Coast Guard's training vessel and

America's tall ship.

|

With Hugh George Campbell's wartime record of captures,

commodores Thomas Tingey and Thomas Truxton saw him as their most

aggressive combat commander. Out of the hundreds of casualties

suffered aboard the American squadron's warships, Campbell's Eagle

reported not one case of illness, disease, injury, drowning, combat

wounds or men killed in action.

This record attests not only to Campbell's good fortune, but his

care and oversight of his ship and crew. On October 16, Campbell

received promotion to captain in the U.S. Navy and would rise to

become a prominent officer in the Navy during the early 1800s. He

was a member of the long blue line and one of America's finest

combat captains in the Age of Sail.

By William H. Thiesen, Atlantic Area Historian, USCG

Provided

through

Coast

Guard

Copyright 2016

Comment on this article |